The outbreak is revealing stark differences between the way Western correspondents and African journalists are able to protect their own health when covering it.

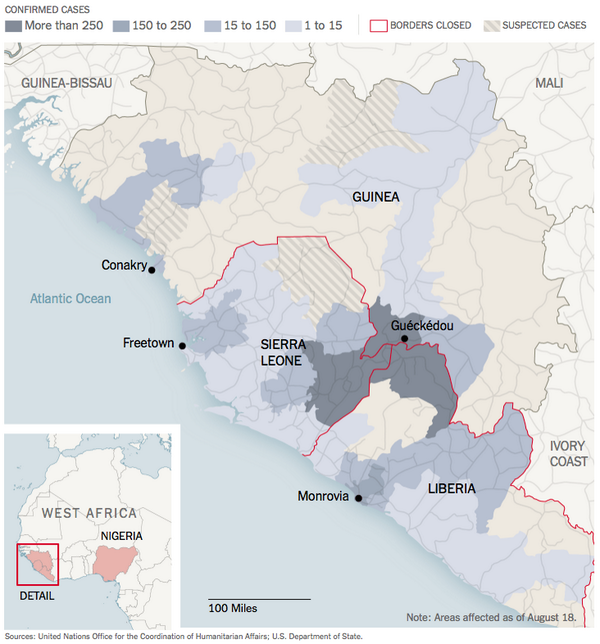

The West African countries which are being plagued by Ebola, such as Liberia and Sierra Leone, are typically economically underdeveloped, and as a consequence their media outlets can’t invest in protective equipment or other pandemic-reporting resources as much as their Western counterparts can.

Additionally, the accountability function of media is less entrenched in many African countries, making access to information in more challenging. In a recent op-ed for The New York Times, Liberia-based journalist Wade C. L. Williams described how she was forced to insist on access to a clinic in Monrovia to carry out her duties. “Fear, misinformation and flat-out denial have been far too common since March, when West Africa’s Ebola outbreak reached Liberia,” she wrote. “Among the government’s first reactions was to limit journalists’ coverage of it. That, in my view, is a major reason the virus has spread as fast as it has.”

Williams told the World Editors Forum that there is not a single journalist who has died as a result of reporting Ebola. “We’ve been lucky,” she said. Her description of the health and safety measures she has in place for reporting Ebola stands in stark contrast to the full protective armour that non-African journalists have access to. “Except for what I read online about the safety measures that are being implemented by everyone here on the ground, I have no particular protective equipment that I use,” she said. “If I go into quarantined areas I normally wash my hands when I come from there in chlorinated water. That is the only protection that I have.”

“If you are going into a hospital, you don’t go into a community where isolated patients are being kept unless you have personal protective equipment, you have to take all the safety measures,” she added. Williams has an international reputation for bravery and courage in her reporting, and she seems unfazed by the dangers she faces entering quarantined areas.

Her editors were unwilling to let her enter an area of Monrovia which is particularly wracked by Ebola, but she resisted: “We had a long argument about me going into West Point, one of the quarantined areas. They were like ‘you can’t go into West Point’, there is a quarantine in there. They were absolutely scared that I was there, I might get infected. I’m like ‘You know, I’m on the ground, I’ve been doing this for the past six months and I’m still here’.”

When epidemics hit developing nations, governments do not merely struggle with the immediate health consequences: scarce resources and a heightened sense of fear mean there can be almost anarchical civil unrest as well. As a consequence, some African journalists covering Ebola have also had to navigate riots and violence, with some suffering serious consequences to their personal safety. Yewa Sandy, a reporter with the Liberian Observer, had her camera confiscated and she received threats from law enforcement while covering a story of a teenager who was shot during a riot. Similarly, the newspaper for which Williams works, FrontPageAfrica, saw another of its reporters (Henry Karmo)arrested and beaten after he took photographs of a protest condemning the Liberian government’s decision to impose a state of emergency.

Western journalists, on the other hand, often benefit from substantial support and training facilitated by their employers designed to protect them from infection. For example, the USA’s National Public Radio (NPR) issued extensive guidelines to its reporter in the field on how to avoid infection. It told him to “not enter isolation units; avoid shaking hands; avoid funerals; avoid eating bush meat; avoid any obvious gatherings/demonstrations; use alcohol-based hand sanitizers”; it also encouraged him to stay “in regular contact by phone, text and email with managers in DC about prospective daily movements”.

Other American publications have followed suit. Ben Solomon, a video journalist at The New York Times, told a question-and-answer session with Reddit that he followed a strict set of health protection protocols. “You don’t shake hands, you wash your feet when you come in and out of rooms. We keep a bottle of chlorine on us at all times and are constantly washing. We probably wash our hands and shoes about 50 times a day.”

Some Western journalists go into the field with so much protection that, ironically, they end up feeling overburdened. Journalist Stephen Douglas, reporting from Sierra Leone for the Toronto Globe and Mail, described how he was “pulling at my plastic hood and trying to get some air down the front of my slippery overalls. It’s hot standing under the sun and it’s very hot under my plastic coverings. My feet ache in the rubber boots that are two sizes too small. My shirt, under the gown, is soaked in sweat and my goggles have fogged up. I’m thankful for an auto-focus lens on my camera.”

NiemanLab, Harvard University’s journalism research centre, has produced a guide for journalists on how to cover epidemics of this kind. Although it includes the caveat that “no one guide can have all the answers to these questions”, the information provided is still extremely detailed. It consists largely of advice from journalists – and others – who have worked in environments which are challenging to health. In particular, the experiences shared by Christy Feig – a former Senior Medical Producer at CNN – support the suggestion that Western journalists are very well-equipped to stay safe when reporting global health crises on-the-ground: “We’ve got Tamiflu stockpiled in certain places and HAZMAT suits in certain places. We train teams in certain areas. We have a doctor on call who will brief anybody before they go in. They are the first people the reporters talk to when they come out. And anyone can decide at any particular time that they don’t want to go in.”

Maggie Fox, who at the time of the guide’s publication was Reuters’ Health and Science Editor, points out that Western journalists often benefit from meticulous planning before they go into the field. “I learned at these flu conferences that if you want people to have good measures to protect themselves, you have to make them make it a habit early on,” she said. “You can’t just wait until the pandemic hits and hand out a bunch of plans and apply them and give people masks and say, “Protect yourselves.” So, I got my editor to put plans in the newsroom.”

Back in Monrovia, Williams remains positive about the mission of African journalists – despite the under-resourcing, health risks and press freedom threats. “My job is to put out the story of those who are behind the quarantine lines, you know?” she says. “You have stories that need to be told.” Thus while there might be differences in the levels of protection the two groups of journalists have, they are united in their mission to report the Ebola story to as wide an audience as they can – in as much detail as they can.

Source: http://blog.wan-ifra.org/2014/08/28/reporting-ebola-a-story-of-divergent-western-and-african-experiences